In September 2024, IMRP Director Andrew Clark and IMRP Director of Research Dr. Vaughn Crichlow, along with leadership from the Connecticut Department of Correction, toured multiple Norwegian correctional facilities, a training facility, as well as a halfway house. The week-long experience built upon previous efforts the IMRP’s International Justice Exchange (IJE) has engaged with to inform best practices in corrections and reentry systems in Connecticut and beyond.

“It’s one thing to read about a system and another to see it. These trips help reimagine what corrections could be and inspire steps for change.” Dr. Vaughn Crichlow, IMRP Director of Research

The Amend Project: A Collaborative Approach

The Amend Project: A Collaborative Approach

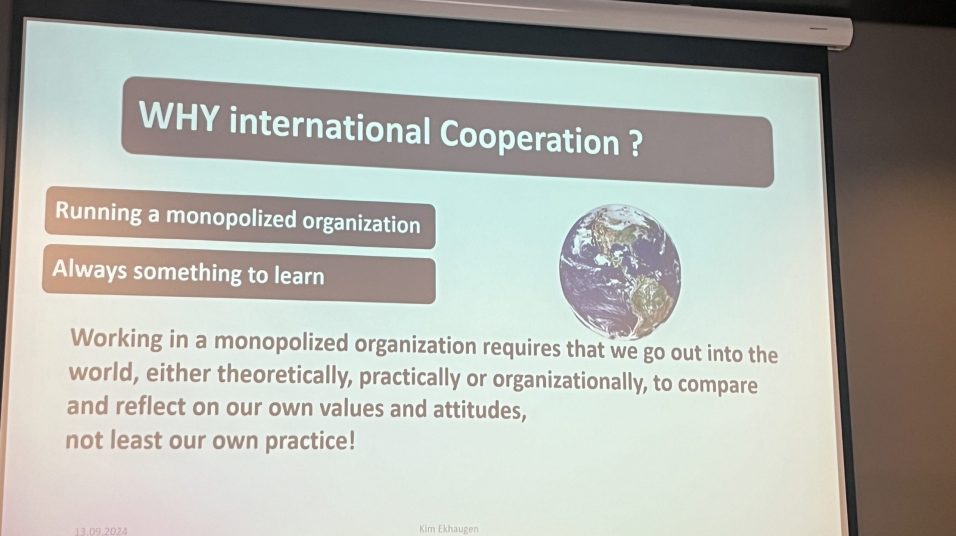

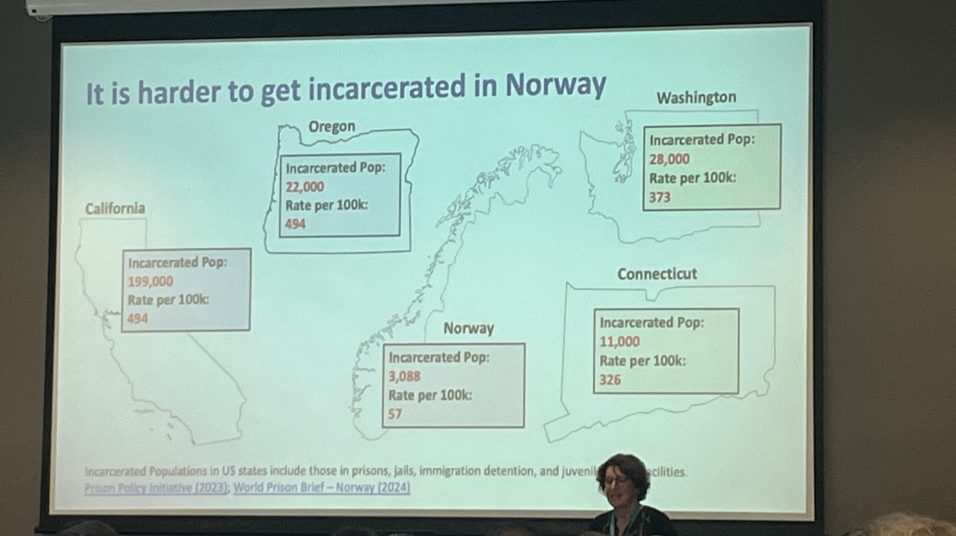

This marked Clark’s second visit to Norway’s carceral system, following his first in 2022, the subject of a CT Public Cutline documentary. The recent trip was organized by The Amend Project, based at the University of California, San Francisco, which fosters cultural transformation in U.S. corrections through the exchange of ideas and best practices. Connecticut is the first East Coast state to participate in this immersion session with Norwegian Correctional Services. Practitioners and policymakers representing California, Oregon, and Washington State were also in attendance. Norway is known for its extremely low incarceration rate and effective prisoner reentry practices. These outcomes result from its rehabilitative approach to corrections. as exemplified by Halden prison, dubbed “the most humane prison in the world.”

These visits strengthen international relationships and deepen understanding of Norway’s correctional philosophy, which emphasizes normalization and community connection. “It’s not just about the system but the society surrounding it,” Clark observed, noting Norway’s general trust in government, commitment to community and embodiment of democratic ideals, all of which lead to a safer overall society.

“As a small country of roughly five million residents, they are also constantly aware of their relationship to the larger world. This is true not only with correctional practices, but also apparent in their commitment to sustainability,” explains Clark, noting that the day he arrived in Bergen, he was made aware that 90% of vehicles sold in Norway that month were electric. “The city streets were quiet, clean, and easy to navigate,” he recalls. “What this impressed on me was a society that was rowing together, having generally embraced a set of priorities based on agreements reached with international partners. Such is true with their commitment to human rights, as reflected in their justice system.”

A Reflection on America’s Influence

“Going into international communities, talking about our system, we don’t really have a sense of what mass incarceration in America has exported to the rest of the world. And I don’t think we should be proud of it,” says Clark, emphasizing the responsibility to do better.

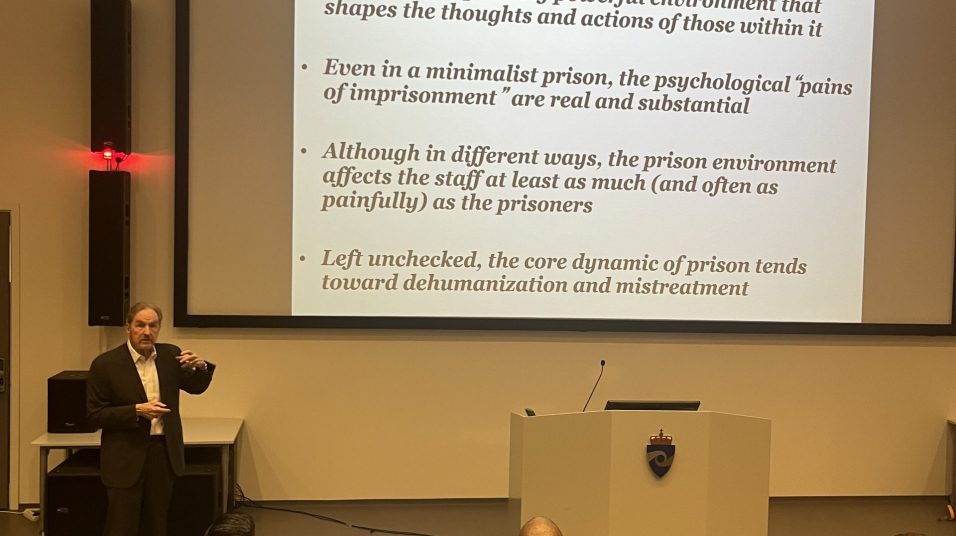

Crichlow adds that Connecticut challenges mirror those faced nationwide. “If you asked any correctional professional in the U.S. whether they believe in rehabilitation, they would likely say yes. But when you examine the spaces they work in and their daily activities, it raises the question: Is this truly rehabilitative? Our environments often retraumatize rather than rehabilitate. Norway shows us that a different approach is possible.”

The Importance of Training and Leadership

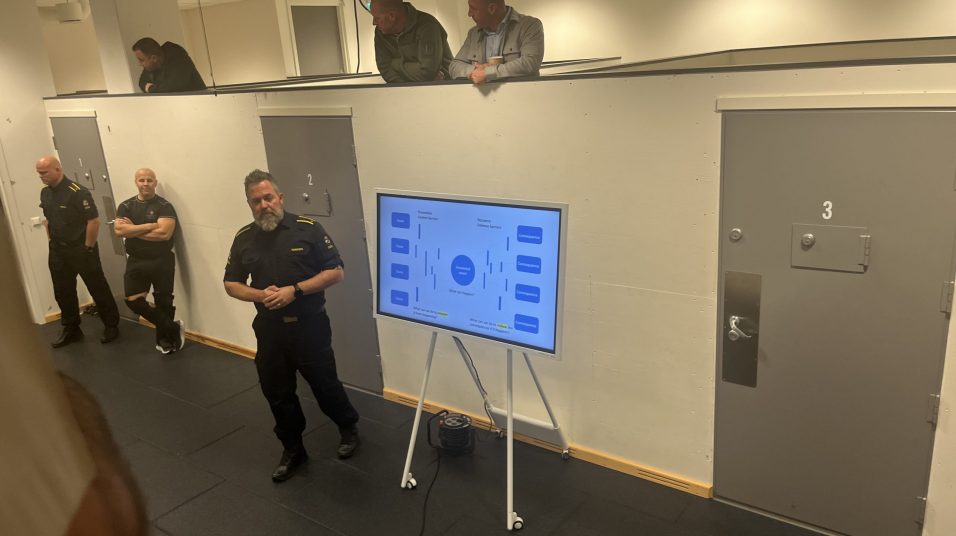

One facility that left a significant impact was the Correctional Service of Norway Staff Academy (KRUS) on Day 4 of the visit.

Unlike Connecticut’s 14–16-week correctional officer training program, Norway’s two-year academy reflects a commitment to thorough professional development, focusing on both inmate and staff health and safety. The program contrasts with the significant public health challenges faced in U.S. corrections, such as the notably low life expectancy of correctional staff, which averages just 59 years.

Normalization in Norway: “Prison Coffee”

One of the most striking aspects of Norway’s system is its emphasis on normalization.

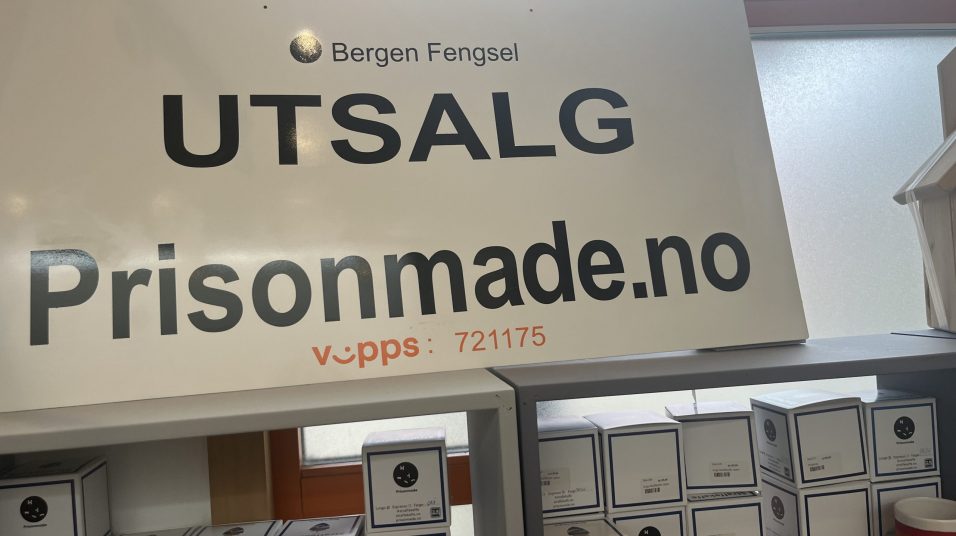

Clark shared an experience at a food festival in Bergen, where incarcerated individuals ran a food truck selling coffee and handmade mugs. Dressed in civilian clothes, they integrated seamlessly into the community. This approach, which fosters integration and reduces stigma, embodies Norway’s commitment to rehabilitation and human dignity.

“What’s fascinating about the system is the focus on keeping the incarcerated population as closely integrated in society as possible,” Clark explained. “Everybody is viewed as a partner in creating safe communities and putting society in balance. It’s a system that demands accountability from everyone.”

The Boat to Bastøy

A standout visit to Bastøy Prison left a lasting impression on Crichlow. Located on an island in the Oslo Fjord, Bastøy operates with minimal fencing and emphasizes trust and self-sufficiency. Inmates run the ferry service as well as maintain the island which is also home to a public beach.

“When we got there, we were looking for the walls and fences and all we say was a little fence and a huge expanse of land,” explains Crichlow. “And one of the first questions we asked was, ‘Aren’t you concerned about people escaping from this facility?’ And it happens every now and then, but they operate on a trust system. They recognize that this is a special place. They have to apply to get here. The know that if they violate the rules, that they would lose the opportunity to be here.”

Trust is fundamental to the success of the Norwegian model. Inmates take on responsibilities such as cooking meals, tending gardens and animals, and disposing of their own trash, tasks similar to those they would have “on the outside.”

“This was paradigm-shifting for me,” Crichlow shares. “The trust system contrasts starkly with the punitive systems in the U.S.”

“We weren’t looking to find the most humane system in the world. We were looking at best practices. And it just so happens that best practices are also the places that have the most humanity.” Andrew Clark, Director, IMRP

Best Practices Rooted in Humanity

Clark emphasized that the search for best practices in corrections naturally leads to more humane systems. “When you remove the adversarial nature that we’ve created in our society, you find that people – regardless of cultural differences – share common desires for health, happiness, and community.” He highlights Norway’s historical shift from a punitive system in the 1980s to one rooted in human rights, influenced by Europe’s legacy of addressing the atrocities of World War II.

“This is an example of a nation and a culture that took steps over time to make change happen,” said Dr. Crichlow, noting the impact of small changes over time. “It’s taken decades for us to get to where we are (in the U.S.). It’s not going to change in a day. But we have to start imagining something different.”

For policymakers and practitioners, the lesson is clear: prioritizing compassion and humanity in corrections yields better outcomes for all. These experiences abroad illuminate the transformative potential of adopting best practices, rooted not just in efficiency but in shared human values. “The flip side of being adversarial is working together,” says Clark. “It’s a fairly basic concept that we understand in so many aspects of our lives and is embedded in our wide scale embrace of team culture – in sports, work, families, or otherwise. The shift here is to recognize that this culture doesn’t need to be sacrificed in a system that also holds people accountable for wrongs they’ve committed.”

“Ultimately,” Clark concludes, “when you educate yourself on what works, it often leads to a direction of compassion, humanity, and improved outcomes for everyone.”

A slideshow of select images is provided below. Another trip through IMRP’s partnership with Amend is planned for September 2025.